Feature Story

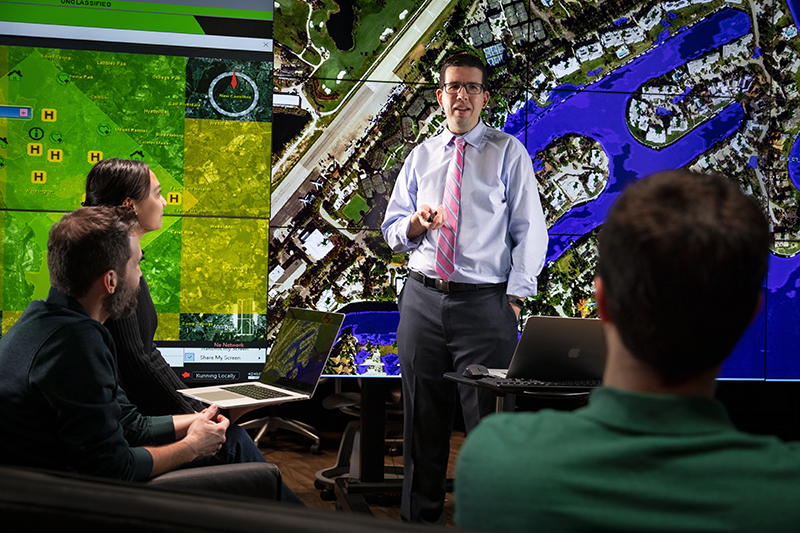

Pedro Rodriguez: Natural Intelligence

A search for precision led Pedro Rodriguez into his career as an electrical engineer, but because of his insights into new possibilities, he now helps lead Johns Hopkins APL’s AI and machine-learning efforts. Today, he sees the potential power and precision of artificial intelligence and machine-learning tools as keys to better protect a changing world.

Fold, tape, flip; fill, fold, tape. Fold, tape, flip; fill, fold, tape.

When Hurricane Maria ravaged the island of Puerto Rico in September 2017, Pedro Rodriguez and his wife, Laura, nervously anticipated word from their loved ones. For two weeks, they waited in the dark. “Like, literally, the entire island disappeared electronically,” Pedro says. “For days.”

While their minds raced, and their nerves frayed, they became cardboard-box-making specialists.

Fold, tape, flip; fill, fold, tape.

They tried to avoid wringing their hands, so instead busied them by making care packages. “We just bought as many supplies as we could. We prepared boxes, and as soon as we heard ‘Post Office open,’ down they went,” Laura recalls.

Canned chicken and vegetables. Batteries. Handheld fans. If they thought it might provide some help, comfort or assistance as their families — and their homeland — recovered from the monstrous Category 5 storm, into the boxes it went.

“Our way of coping,” Laura says, “was to try to help.”

Perhaps, then, it’s not surprising that more than three years later, Pedro Rodriguez finds his professional expertise has enabled him to expand that ethos to a grander scale.

As the senior technical leader of multiple deep learning artificial intelligence projects at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, Pedro has a vast portfolio. One highlight is APL’s Humanitarian Assistance for Disaster Relief program, a machine-learning and artificial intelligence-enabled program to collect and process overhead imagery into categories for analysis. It allows disaster recovery teams to assess in hours what has previously taken days, or sometimes weeks.

HADR, as the program is known, processes flood segmentation (locating and marking areas of flooding), road analysis (identifying blocked and unblocked roads), and building damage assessment. That last one, which classifies buildings based on the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) protocol, categorizes structures into no damage, minor damage, major damage and completely destroyed.

In partnership with the Department of Defense’s Joint Artificial Intelligence Center, HADR was pressed into service to aid FEMA’s recovery efforts after 2018’s Hurricane Florence and 2019’s Hurricane Dorian devastated parts of the U.S. and the Caribbean islands. It was called to action in 2020 after Hurricane Laura, a deadly and destructive Category 4 storm, battered Louisiana.

“It was coincidence,” Pedro explains of the link between his professional project and his personal hurricane history, noting APL was able to quickly leverage technology developed for another project when the light bulb went off that it could dramatically assist in these situations.

“But now, we are all in.”

Experiencing hurricanes, knowing especially what my family went through most recently, has played a huge role in my enthusiasm for this project. Once we started using this technology for disaster relief applications, I just knew it was an area we could profoundly impact.

The silence that turned Pedro and Laura into mailing mavens finally broke after a couple of weeks. One of Pedro’s aunts was able to drive to a specific spot on the island where she’d search for cell phone service and send word that, fortunately, all were OK. After two weeks, the landline in Laura’s mom’s house started working again, and neighbors she hadn’t seen in years lined up at her door to ask for its use.

Pedro’s lasting impression of his first visit back after Maria was visual. “There was no green,” he says, all the trees and bushes left bare from the storm.

Studies show that occurrences and strengths of major hurricanes are expected to increase as the planet warms. In 2020, there were a record 30 named storms during the Atlantic hurricane season. Personal experiences aside, the world’s ability for people, states and countries to recover from these dangerous events is, and will continue to be, paramount. Pedro knows that.

“Experiencing hurricanes, knowing especially what my family went through most recently, has played a huge role in my enthusiasm for this project,” he says. “Once we started using this technology for disaster relief applications, I just knew it was an area we could profoundly impact.

“I want this to be a strength of our group for a long, long time.”

It was the search for precision that led Pedro Rodriguez, an electrical engineer in a family of civil engineers (and one accountant), to machine learning and image recognition. Once, in an electromagnetic class in college at the University of Puerto Rico, he was designing an antenna for radar that wasn’t working quite right. His professor took a look and devised a quick fix.

“He pulled out a knife and cut a piece of the antenna off,” Pedro recalls. “And suddenly, it worked. I was like, ‘Are you kidding me? Is this really engineering?’ The fact that it was not perfect, it freaked me out. To me, pixels in digital images are perfection.”

I’ve heard people say he is the OG — the original gangster — of transfer learning here at the Lab. He was doing deep learning before it was cool.

About 10 years ago, before deep learning, machine learning and artificial intelligence were as commonly interspersed into the public lexicon, Pedro was a young(er) engineer focused on transfer learning — training a neural network on a problem similar to the one you’re trying to solve, then applying part of it in a new model on the actual problem.

“I’ve heard people say he is the OG — the original gangster — of transfer learning here at the Lab,” Ryan Amundsen, a signal processing engineer at APL and a mentee of Pedro’s, says with a chuckle. “He was doing deep learning before it was cool.”

“Because of how smart he is and his outgoing nature, I see Pedro as the person who kind of brought computer vision to the Lab for AI purposes,” added Dean Fisher, who manages the Tactical Intelligence Systems Group at APL, putting Amundsen’s observation in, perhaps, more formal terms.

Credit: Johns Hopkins APL

“When deep learning came about, I recognized that I could do with deep learning neural networks what I was doing with this other thing, called HMAX [Hierarchical Model and X],” Pedro explained. “The cool part was that it was like a one-week fix, and the results were immediately 20-40% better.”

PedroNet — a grayscale, deep learning neural network that Pedro trained himself in APL’s maker space, Central Spark — was born. And his profile within the Laboratory skyrocketed.

“Word got around really fast,” Pedro recalls of the interest in his work. “I was literally walking around with PowerPoints, showing it to people.”

Pedro had wanted to be an astronaut and applied to NASA’s program (before completing his Ph.D.). He was introduced to the Laboratory (and his wife, who works as a systems accountant at APL) through an undergraduate internship at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, a short distance from the Laboratory. His career, which he put on a beeline for the Lab after that initial taste from Goddard, began with work on classified projects in APL’s Force Projection Sector, where PedroNet came about. For now, Pedro is no closer to his goal of being an astronaut, and he’s still never worked in the Lab’s Space Exploration Sector.

In many ways, the successes that led him here — now a prominent voice in the Laboratory’s AI and machine-learning efforts — have come because of paths that diverged from their originally planned end point.

That was the antithesis of what he sought as a young professional. Pixels with a set value, processes that return specific — expected — results; these unshakeable constants lured him. “Even though machine learning has some ambiguity to it, I remember feeling a sense of calm when I gravitated toward this field and computer vision.”

PedroNet, a microexample of his technical acumen, was part of what launched him on his current trajectory. His gregarious personality, introspective nature and unapologetic ambition helped too.

I think much of it comes back to the question of ‘What do you have to do to be world-class?’ You identify what you need to do and you do it. That’s Pedro in a nutshell.

“He was so open about sharing his knowledge and insight [that] people sought him out as the subject-matter expert in this emerging area,” Fisher said. “But you see the impact now with the many premier programs the Lab is working on. That’s all part of [APL Director] Ralph Semmel’s strategic vision to make APL an AI center of excellence. Pedro’s contributions there have been tremendous, and it started with collaboration and his willingness to share.”

“I think much of it comes back to the question of ‘What do you have to do to be world-class?’” added John Piorkowski, the chief AI architect in APL’s Asymmetric Operations Sector and head of its Applied Information Sciences Branch, of which Pedro’s group is a part. “You identify what you need to do and you do it. That’s Pedro in a nutshell. He will put his mind to something and work to achieve it.”

On a frigid afternoon in mid-January 2020, Pedro pulls out his smartphone and drops it on the table in his office at APL’s suburban Maryland campus. To his right, a whiteboard displays work-related scribbles on its upper half and a DO NOT ERASE warning for the content below it — self-portraits of sorts drawn by his daughters, Natalia and Elena. Tiny reminders of his world outside these walls.

Open on the screen of his phone is QuakeFeed Earthquake Alerts, an app monitoring earthquake activity around the world. A larger reminder of that same world. Pedro’s filtering it to only show quakes registering 4.0 or higher on the Richter scale since Dec. 28.

Credit: Pedro Rodriguez

He turns the phone.

“This is where all my family is,” he says, zooming in on southwest Puerto Rico and the area where his hometown, Guanica, sits facing the Caribbean Sea. Red pins flood the region. His fingers tap the screen, removing the 4.0 or higher qualification, and the pins, denoting earthquakes, proliferate.

“Look at this,” he says, his tone escalating with each finger stroke as he moves the map around. “It is crazy. What the heck is this? When is it going to end? It feels like, every time it shakes, the damage caused takes the next step to being worse than Hurricane Maria.”

That is not a comparison Pedro makes lightly, particularly not after visiting Puerto Rico himself later that January and experiencing the aftershocks and tremors the locals understood could go on for a year or more. “The randomness of destruction was shocking,” he said. “It was weird to see a house completely destroyed and the house next to it perfectly fine. That just did not compute in my mind. What is the difference between this house and that house?”

This destruction was loud; it was obvious. Disasters are like that, Pedro knows. He may not have been on the island during Maria, but he’s certainly experienced his share of hurricanes. It is, oddly, the quiet that Pedro remembers most about them.

Even now, more than two decades after Hurricane Georges ripped through his hometown, it’s not the destructive force of the 140-mph wind gusts, the driving rains and flooding, or the catastrophic damage that spring to his mind first. It is serenity. The tranquility of a sky suddenly so clear he and his brother walked outside to stare up, through Georges’ eye as it passed over their house, and gaze at the moon in the silence.

“It was like the most beautiful night,” he says. “If it had been daytime, the sun would’ve shone on us.”

The peacefulness didn’t last — in part because the second wall of the storm was about to shatter its illusion, but, more to the point, because his father came running out of the house to corral his children back into the safety of its concrete walls. Minutes later, the storm’s pounding resumed. Their home was spared, but the family suffered through six months without power or water.