Press Release

APL Researchers Suggest New Picture of the Sun’s Interaction with the Galaxy

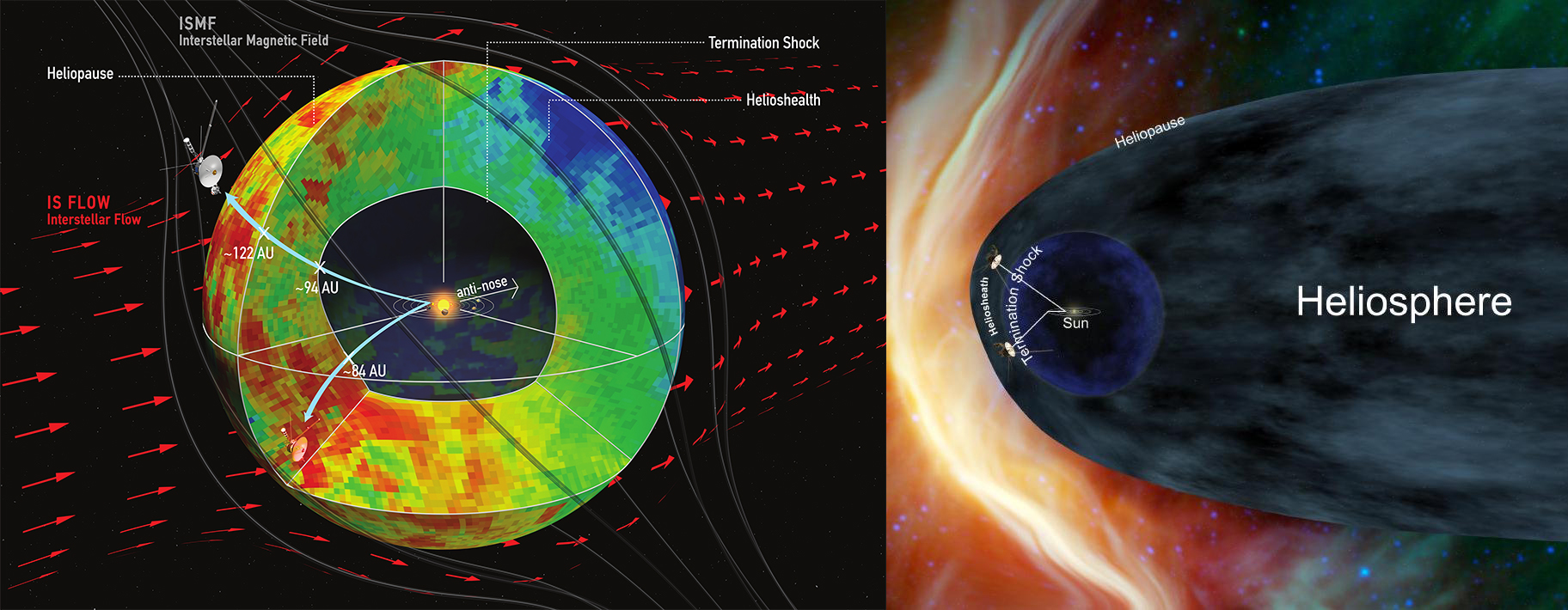

New data from Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) experiments on NASA’s Cassini and Voyager spacecraft, combined with measurements from NASA’s Interstellar Boundary Explorer, suggests that the heliosphere — the bubble of the sun’s magnetic influence that surrounds the inner solar system — may be much more compact and rounded than previously thought.

The sun releases a constant flow of magnetic solar material — called the solar wind — that fills the inner solar system, reaching far past the orbit of Neptune. This solar wind creates a bubble, some 23 billion miles across, called the heliosphere. Our entire solar system, including the heliosphere, moves through interstellar space. The prevalent picture of the heliosphere was one of a comet-shaped structure, with a rounded head and an extended tail. But new data covering an entire 11-year solar activity cycle shows that may not be the case: in fact, the heliosphere may be rounded on both ends, making its shape almost spherical.

Researchers published these findings today in the journal Nature Astronomy.

“Instead of a prolonged, comet-like tail, this rough bubble-shape of the heliosphere is due to the strong interstellar magnetic field — much stronger than what was anticipated in the past — combined with the fact that the ratio between particle pressure and magnetic pressure inside the heliosheath is high,” said Kostas Dialynas, a space scientist at the Academy of Athens in Greece and lead author on the study.

The APL-built Magnetospheric Imaging Instrument (MIMI) on Cassini, which has been exploring the Saturn system over a decade, has given scientists crucial new clues about the shape of the heliosphere’s trailing end, often called the heliotail. When charged particles from the inner solar system reach the boundary of the heliosphere, they sometimes undergo a series of charge exchanges with neutral gas atoms from the interstellar medium, dropping and regaining electrons as they travel through this vast boundary region. Some of these particles are pinged back toward the inner solar system as fast-moving neutral atoms, which Cassini can measure.

“Our Cassini instrument was designed to image the ions that are trapped in the magnetosphere of Saturn,” said APL’s Tom Krimigis, an instrument lead on the Cassini and Voyager missions and an author on the study. “We never thought that we would see what we’re seeing and be able to image the boundaries of the heliosphere.”

Because these particles move at a small fraction of the speed of light, their journey from the sun to the edge of the heliosphere and back takes years. So when the number of particles coming from the sun changes — usually as a result of its 11-year activity cycle — it takes years before that’s reflected in the amount of neutral atoms shooting back into the solar system.

Cassini’s new measurements of these neutral atoms revealed something unexpected — the particles coming from the tail of the heliosphere reflect the changes in the solar cycle almost exactly as fast as those coming from the nose of the heliosphere.

“If the heliosphere’s ‘tail’ is stretched out like a comet, we’d expect that the patterns of the solar cycle would show up much later in the measured neutral atoms,” said Krimigis.

But because patterns from solar activity show just as quickly in tail particles as those from the nose, that implies the tail is about the same distance from us as the nose. This means that long, comet-like tail that scientists envisioned may not exist at all — instead, the heliosphere may be nearly round and symmetrical.

A rounded heliosphere could come from a combination of factors. Data from Voyager 1 — including that gathered with APL’s Low-Energy Charged Particle (LECP) instrument — show that the interstellar magnetic field beyond the heliosphere is stronger than scientists previously thought, meaning it could interact with the solar wind at the edges of the heliosphere and compact the heliosphere’s tail.

The structure of the heliosphere plays a big role in how particles from interstellar space — called cosmic rays — reach the inner solar system, where Earth and the other planets are.

“This data that Voyager 1 and 2, Cassini and IBEX provide to the scientific community is a windfall for studying the far reaches of the solar wind,” said Arik Posner, Voyager and IBEX program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., who was not involved with this study. “As we continue to gather data from the edges of the heliosphere, this data will help us better understand the interstellar boundary that helps shield the Earth environment from harmful cosmic rays.”