Revolutionizing Prosthetics

Research

The Revolutionizing Prosthetics program started in 2006 with an aim to provide functional restoration for individuals with amputation and other conditions that limit upper-limb control. Under this multifaceted research and development effort, the greater team focused on a number of critically enabling capabilities, which included the Modular Prosthetic Limb (MPL), the muscle/neural signal acquisition and processing pipeline, and the Virtual Integration Environment (VIE).

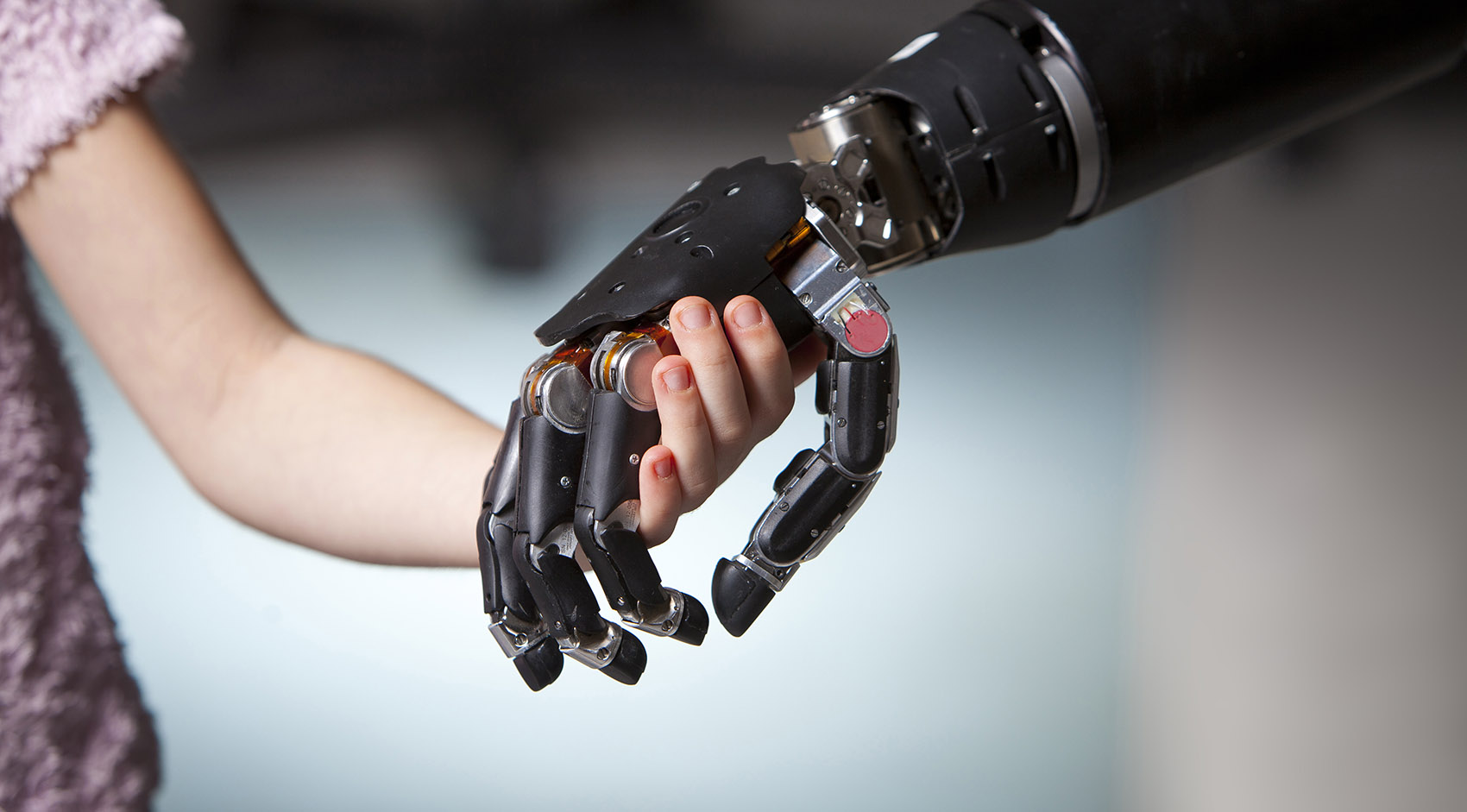

Capable of effectuating almost all of the movements as a human arm and hand and with more than 100 sensors in the hand and upper arm, the Modular Prosthetic Limb (MPL) is the world’s most sophisticated upper-extremity prosthesis. There are currently ten MPLs being used for neurorehabilitation research across the United States.

The MPL features:

- Anthropomorphic (lifelike) form factor and appearance

- Human-like strength and dexterity

- High-resolution tactile and position sensing

- Neural interface for intuitive and natural closed-loop control

Sensorization

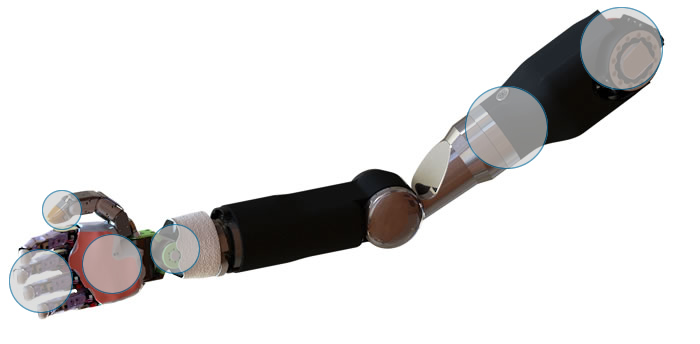

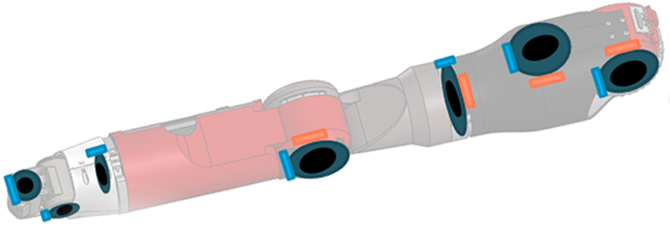

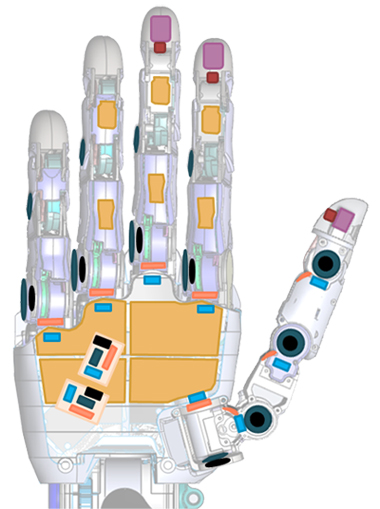

The arm and hand pictured below contain more than 100 sensors. Many candidate technologies were prototyped and evaluated by using a custom test bed and standardized processes. In addition to sensor-specific performance criteria, other design constraints included integration, reliability, and manufacturability. At the individual joints, sensors measure angle, velocity, and torque. Additional sensors at the fingertip measure force, vibration, fine point contact, and temperature/heat flux.

Key, Sensor, and Number

- *Additional sensors include: incremental rotor position (x17); drive voltage (x17); and upperarm drive current (x7)

General Specifications

| Parameter | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Degrees of Freedom | 26 | DOF |

| Motors (Degree of Control) | 17 | DOC |

| Onboard Motor Controllers | Custom Embedded | |

| Onboard Sensor Conditioning and Digitization | Custom Embedded | |

| Mass of Hand and Wrist | 2.9 | lbs |

| Mass of Upper Arm with Battery | 7.6 | lbs |

| Payload Capacity (Wrist Active) | 15 | lbs |

| Payload Capacity (Wrist Static and Upper Arm Active) | 35 | lbs |

| Cylindrical Grasp Force | 70 | lbf |

| Two-Jaw Pinch Force | 15 | lbf |

| Three-Jaw Chuck Pinch Force | 25 | lbf |

| Lateral Key-Pinch Force | 25 | lbf |

| Upper Arm Joint Speed | 120* | deg/s |

| Wrist Joint Speed | 120* | deg/s |

| Hand Open or Close Time | 300 | ms |

| Voltage | 24 | volts |

| Communications | CAN |

Body Attachment

Development of a comfortable yet robust body attachment to support the range of movement and load capacity of the MPL for varying amputation levels was accomplished through investigation of multiple volume accommodating and dynamic shape-changing socket methods. These included pneumatic or air-filled bladders, hydraulic or fluid-filled bladders, vacuum-attachment methods, electro-active polymers, and shape-changing material structures. Improved surface electromyographic electrodes enhance patient comfort, and static and dynamic load distribution can be accommodated with liners, counterbalances, dynamically adapting elements, and active vacuums. Additional socket design challenges were driven by the need to provide space for controllers, for the tactor or other afferent devices, and for peripheral control (Implantable Myoelectric Sensor [IMES] and Utah Slanted Electrode Array [USEA]) transduction elements.

Development of a comfortable yet robust body attachment to support the range of movement and load capacity of the MPL for varying amputation levels was accomplished through investigation of multiple volume accommodating and dynamic shape-changing socket methods. These included pneumatic or air-filled bladders, hydraulic or fluid-filled bladders, vacuum-attachment methods, electro-active polymers, and shape-changing material structures. Improved surface electromyographic electrodes enhance patient comfort, and static and dynamic load distribution can be accommodated with liners, counterbalances, dynamically adapting elements, and active vacuums. Additional socket design challenges were driven by the need to provide space for controllers, for the tactor or other afferent devices, and for peripheral control (Implantable Myoelectric Sensor [IMES] and Utah Slanted Electrode Array [USEA]) transduction elements.

Recommended Reading

- Revolutionizing Prosthetics 2009 Modular Prosthetic Limb–Body Interface: Overview of the Prosthetic Socket Development (Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Volume 30, Issue 3, pp. 240–249, 2011)

Cosmesis

The basic requirements for the Revolutionizing Prosthetics cosmesis are that it appear natural, be durable, be able to be manufactured, have minimal weight, meet mechanical requirements (such as minimizing energy consumption due to drag of the cosmesis to extend the operating time of the battery), support sensor function, and be repairable. Acting as an initial barrier against the environment and allowing sensors to measure force, vibration, and temperature through the cosmesis are additional requirements. Two variations of the MPL cosmesis were developed: the work glove, a functional covering that is less expensive and more durable, and the standard glove, a fully realistic cosmetic cover that includes artistic detailing to resemble a natural limb and spectrally insensitive color formulations (metamerism).

The basic requirements for the Revolutionizing Prosthetics cosmesis are that it appear natural, be durable, be able to be manufactured, have minimal weight, meet mechanical requirements (such as minimizing energy consumption due to drag of the cosmesis to extend the operating time of the battery), support sensor function, and be repairable. Acting as an initial barrier against the environment and allowing sensors to measure force, vibration, and temperature through the cosmesis are additional requirements. Two variations of the MPL cosmesis were developed: the work glove, a functional covering that is less expensive and more durable, and the standard glove, a fully realistic cosmetic cover that includes artistic detailing to resemble a natural limb and spectrally insensitive color formulations (metamerism).

Recommended Reading

- An Overview of the Developmental Process for the Modular Prosthetic Limb (Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Volume 30, Issue 3, pp. 207–216, 2011)

- The Cosmesis: A Social and Functional Interface (Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Volume 30, Issue 3, pp. 250–255, 2011)

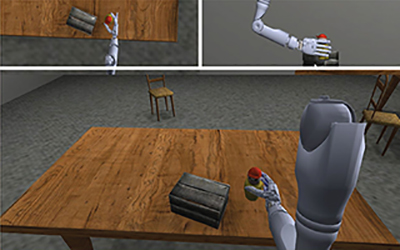

Because of the limited quantities of the Modular Prosthetic Limb (MPL), APL developed a virtual-reality MPL that runs in the Virtual Integration Environment (VIE). The VIE was developed to make the transition from a virtual training environment to the physical world with the actual MPL as seamless as possible, thus facilitating patient training for optimal control of the prosthetic limb. Importantly, the VIE is a platform-independent communication interface to the MPL. It offers an improved three-dimensional MPL simulation environment.

Because of the limited quantities of the Modular Prosthetic Limb (MPL), APL developed a virtual-reality MPL that runs in the Virtual Integration Environment (VIE). The VIE was developed to make the transition from a virtual training environment to the physical world with the actual MPL as seamless as possible, thus facilitating patient training for optimal control of the prosthetic limb. Importantly, the VIE is a platform-independent communication interface to the MPL. It offers an improved three-dimensional MPL simulation environment.

The VIE was created as a development platform for rapid prototyping, evaluation, and deployment of neural signal processing algorithms.

- Based on MATLAB xPC Target; operates in (hard) real time

- Accepts inputs from Cerebus, Plexon, Vikon, etc.

- Defines standard input/output interfaces for neural signal analysis algorithms (neural signals in/limb commands out)

- Can simulate an electromechanical system with or without hardware

- Provides three-dimensional visualization and a configurable interactive world via Unity/PhysX

Recommended Reading

- Development of Virtual Integration Environment Sensing Capabilities for the Modular Prosthetic Limb (Society for Neuroscience, Washington, DC, 2014)

- Use of a Virtual Integrated Environment in Prosthetic Limb Development and Phantom Limb Pain (Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, Volume 181, pp. 305–309, 2012)

- A Real-Time Virtual Integration Environment for Neuroprosthetics and Rehabilitation (Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Volume 30, Issue 3, pp. 198–206, 2011)

- Using a Virtual Integration Environment in Treating Phantom Limb Pain (Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, Volume 163, pp. 730–736, 2011)

- A Real-Time Virtual Integration Environment for the Design and Development of Neural Prosthetic Systems (Conference Proceedings: Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–25 August 2008, pp. 615–619)

Revolutionizing Prosthetics developed a robust hybrid neural interface approach that capitalized on the strengths of individual signal sources and provided a flexible solution set suitable for a breadth of injuries. Sensory feedback is crucial for effective performance of daily activities, so the fully sensorized limb system supported biofidelic feedback options consistent with the hybrid strategy for closed-loop control.

Several types of recording devices were used to record various biological signals from muscles, peripheral nerves, and the cortex for the purpose of motor decoding. Implanted intramuscular electrodes and surface electromyogram electrodes were used to record muscle activity; implantable peripheral nerve electrode intercepted signals, propagating along peripheral nerves; and implantable cortical electrode captured spike and local field potentials, near their origins in the primary motor, premotor, and posterior parietal cortices. Collecting all of these signal modalities provided complementary information as well as a certain level of redundancy that maintained long-term high levels of fidelity and provided modularity. This was especially important because we addressed tetraplegic patients and the full range of upper-extremity amputees—to include shoulder, transhumeral, transradial, and wrist disarticulations in addition to normal interpatient variations. We had a robust neural interface strategy with a strong cortical focus, and support for noninvasive or minimally invasive integration methods as well.

The Revolutionizing Prosthetics program developed neural decoding algorithms that translated electrical signals received from the body into commands for the limb systems or other devices. These algorithms were all supervisory, requiring a representative data set of the desired commands to “train” the algorithms. The signals used for decoding (e.g., electromyographic action potentials, etc.) had a significant impact on the training data and therefore influenced the choice for the best type of algorithm. In addition, the complexity of the desired movement drove the complexity and size of the training data and thus the complexity of the algorithm. Finally, the algorithms were designed with computational and memory constraints in mind, making linear algorithms the most frequently used.

Recommended Reading

- Control System Architecture for the Modular Prosthetic Limb (Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Volume 30, Issue 3, pp. 217–222, 2011)

- Revolutionizing Prosthetics: Neuroscience Framework (Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Volume 30, Issue 3, pp. 223–229, 2011)

- Revolutionizing Prosthetics: Devices for Neural Integration (Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Volume 30, Issue 3, pp. 230–239, 2011)

Johns Hopkins Medicine and APL collaborated on the use of the Modular Prosthetic Limb (MPL) and targeted muscle reinnervation (TMR) surgery.

TMR is a surgical procedure that reassigns nerves that once controlled the arm and the hand. By reassigning existing nerves, doctors can make it possible for people who have had upper-arm amputations to control their prosthetic devices by merely thinking about the action they want to perform. Once experimental, this innovative procedure is now available at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. People who underwent the targeted reinnvervation surgery were fitted with and trained to use a myoelectric prosthetic arm.

Watch the 60 Minutes report, “Breakthrough: Robotic limbs moved by the mind”

APL collaborated with the Department of Surgery at Johns Hopkins Medicine on clinical trials using the MPL for patients who received TMR surgery.

Who Might Benefit from TMR Surgery?

Those interested in the procedure to better control their prosthetic arm must undergo a medical review to determine their eligibility. In general, patients must meet the following criteria:

Those interested in the procedure to better control their prosthetic arm must undergo a medical review to determine their eligibility. In general, patients must meet the following criteria:

- Amputation above the elbow or at the shoulder within the last 10 years

- Stable soft tissues

- Willingness to participate in rehabilitation

Those who were born without part or all of their arm and those who have nerve damage, degeneration, or paralysis are not candidates for this procedure.

TMR is a specialized surgical procedure developed by the expert staff at Johns Hopkins Medicine, including Albert Chi, M.D., the Medical Director for the Targeted Muscle Reinnervation Program. Dr. Chi also serves Assistant Professor of Surgery at Johns Hopkins Medicine. He is a trauma surgeon whose practice includes critical care, trauma, and acute care surgery. He has a background in biomedical engineering, and his clinical research is focused on improving the lives of individuals with traumatic injuries, with an emphasis on motor control. Dr. Chi is also commissioned as a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Navy Reserve and is dedicated to serving our country and helping care for the wounded warriors returning home and those injured in the field.

For more information regarding TMR surgery or to schedule an appointment, please call Johns Hopkins Medicine at 443-287-0618 or visit the Johns Hopkins Medicine Department of Surgery website.

A study at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center to assess the functionality of the Modular Prosthetic Limb was expanded to include civilian in addition to military amputees. Several spin-off projects also took off. Working with Second Sight, the team developed the Hybrid Augmented Reality Multimodal Operation Neural Integration Environment—HARMONIE—a semiautonomous controller for assistive robotic manipulators and remote devices.

Johns Hopkins Medicine Department of Surgery

- Dr. Pablo Celnik (Johns Hopkins University)

- The Human Brain Physiology and Stimulation Laboratory

- Focused on studying the mechanisms underlying motor learning and developing interventions to modulate motor function in humans

- Targeted Muscle Reinnervation (TMR)

Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Department of Surgery

- Dr. Albert Chi (Oregon Health & Science University)

- Associate Professor of Surgery, OHSU

- Medical Director, OHSU Targeted Muscle Reinnervation Program

- Research and Exploratory Development Department, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory

- Commander, United States Navy Reserves

Other Revolutionizing Prosthetics Related Efforts

California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and Los Amigos Rancho Rehabilitation Research Institute, Inc. (LAREI)

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (through the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine)

- Recruiting Information: Virtual Integrated Environment in Decreasing Phantom Limb Pain (VIE)

Related Clinical Trials

- BrainGate2: Feasibility Study of an Intracortical Neural Interface System for Persons with Tetraplegia (Massachusetts General Hospital)

- Implanted Myoelectric Control for Restoration of Hand Function in Spinal Cord Injury (MetroHealth Medical Center)

NIH-Sponsored Research

- Clinical Demonstration of Implantable Myoelectric Sensors for Prosthesis Control (University of Colorado Denver)

- Cortical Control of an Assistive Robotic Arm (Brown University)

- Model-Based Training for BCI Rehabilitation (University of Pittsburgh)

- Multigrasp Myoelectric Control of a Hand Prosthesis, and Assessment of Efficacy (Vanderbilt University)

- Targeted Reinnervation and Pattern-Recognition Control for Transradial Amputees (Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago)

Clinician Resources

With 17 degrees of freedom and more than 100 sensors in the hand and upper arm, the Modular Prosthetic Limb (MPL) is the world’s most sophisticated upper-extremity prosthesis. There are currently ten MPLs being used for research purposes across the United States. Because of the limited quantities of the device, APL developed a virtual-reality MPL that runs in the Virtual Integration Environment (VIE). The VIE was developed to make the transition from a virtual training environment to the physical world with the actual MPL as seamless as possible, thus facilitating patient training for optimal control of the prosthetic limb. The VIE translates control signals into limb movements and displays a virtual model of these movements. In this environment, patients can test-drive limbs and provide feedback while still in the recovery stage or while a prosthetic arm is manufactured and fitted. The clinician interface to the VIE allows limb configuration parameters to be tuned for each patient in order to achieve maximum performance.

APL provides the VIE to clinicians and researchers through a no-cost licensing agreement. As of June 2014, sixteen institutions across the world have signed these agreements in applications focused on improvements in myoelectric, electrocorticographic, and cortical control open-loop and closed-loop studies.

Recommended Reading

- A Real-Time Virtual Integration Environment for Neuroprosthetics and Rehabilitation (Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Volume 30, Issue 3, pp. 198–206, 2011)

Publications

Explore publications from the Revolutionizing Prosthetics program.

Beyond Intuitive Anthropomorphic Control: Recent Achievements Using Brain Computer Interface Technologies

Pohlmeyer EA, Fifer M, Rich M, Pino J, Wester B, Johannes M, Dohopolski C, Helder J, D’Angelo D, Beaty J, Bensmaia S, McLoughlin M, Tenore F

Proc. SPIE, 10194:101941N, doi: 10.1117/12.2263886 (2017)

Chronic Intracortical Recordings from Microelectrode Arrays Implanted in Common Marmosets (Callithrix jacchus)

Debnath S, Prins NW, Mylavarapu R, Pohlmeyer EA, Geng S, Sanchez JC, Prasad A

Society for Neuroscience, Washington, DC, 2017

Common Marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) as a Primate Model for Behavioral Neuroscience Studies

Prins NW, Pohlmeyer EA, Debnath S, Mylavarapu R, Geng S, Sanchez JC, Rothen D, Prasad A

J Neurosci Methods, 284:35–46, doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.04.004 (2017)

Comparison of Pattern Recognition Control with a Socket and with an Osseointegration Implant: A Case Report

Carroll LM, Johannes MS, Moran CW, Armiger RS

Seventh International Conference: Advances in Orthopaedic Osseointegration, San Diego, CA, 12–13 March 2017

Development of an Osseointegration Interface for a Dexterous Prosthetic Limb

Carroll LM, Johannes MS, Armiger RS

Seventh International Conference: Advances in Orthopaedic Osseointegration, San Diego, CA, 12–13 March 2017

The EyeFlight Project: Identifying Markers of Cognitive Workload Non-Invasively

Scholl CA, Pohlmeyer EA, Rich MJ, Fifer MS, Jessee MS, Wester BA, Chevillet MA, Moran JM, Hwang GM, Tenore FV

88th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Aerospace Medical Association, Denver, CO, 30 April – 4 May 2017

Flight Simulation Using a Brain-Computer Interface: A Pilot, Pilot Study

Kryger M, Wester B, Pohlmeyer EA, Rich M, John B, Beaty J, McLoughlin M, Boninger M, Tyler-Kabara EC

Experimental Neurology, 287:473–478, doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.05.013 (2017)

Initial Clinical Evaluation of the Modular Prosthetic Limb System for Upper Extremity Amputees

Yu KE, Pasquina PF, Moran CW, Armiger RS, Johannes MJ

Military Health System Research Symposium, Orlando, FL, 27–30 August 2017

Initial Clinical Evaluation of the Modular Prosthetic Limb System for Upper Extremity Amputees

Yu KE, Pasquina PF, Moran CW, Armiger RS, Johannes MJ

Myoelectric Controls Symposium, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada, 15–18 August 2017

Load and Torque Characteristics of an Upper Limb Osseointegration Implant during Use

Carroll LM, Johannes MS, Moran CW, Armiger RS

Seventh International Conference: Advances in Orthopaedic Osseointegration, San Diego, CA, 12–13 March 2017

Mind Flight: Brain-Computer Interface-Driven Design of Simulated Aircraft Control Frameworks

Johnson B, Wester B, Cybyk D, Handelman D, D’Angelo D, Pohlmeyer E, Tenore F, Beaty J, Pino J, Ellsworth J, Fifer M, Rich M, McLoughlin M, Turner N, Ide R, Koterba Z

Interservice/Industry Training, Simulation, and Education Conference (I/ITSEC), Orlando, FL, 27 November – 1 December 2017

Motor Cortex Spiking and Local Field Potentials (LFP) during a Reaching Task in Common Marmosets (Callithrix jacchus)

Mylavarapu R, Prins NW, Debnath S, Castro A, Geng S, Pohlmeyer EA, Sanchez JC, Prasad A

Society for Neuroscience, Washington, DC, 2017

Navigating a Virtual Environment Using Intracortical Microstimulation of Human Somatosensory Cortex

Pohlmeyer EA, Fifer MS, Bensmaia SJ, Rich M, Pino J, Flesher SN, Weiss JM, Collinger JL, Gaunt RA, Beaty J, McLoughlin M, Tenore F

Society for Neuroscience, Washington, DC, 2017

An Objective Classifier of Expertise in United State Marine Corps Combat Aviators

Nozima AM, Martinez-Conde S, Castro JI, DiStasi LL, McCamy MB, Gayles E, Cole AG, Foster MJ, Hoare B, Tenore F, Jessee MS, Pohlmeyer E, Chevillet M, Catena A, DeSouza WC, Janczura GA, Macknik SL

Society for Neuroscience, Washington, DC, 2017

Targeted Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation for Phantom Limb Sensory Feedback

Osborn L, Fifer M, Moran C, Betthauser J, Armiger R, Kaliki R, Thakor N

13th IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), Turin, Italy, 19–21 October 2017, doi: 10.1109/BIOCAS.2017.8325200

Classification of Pilot-Induced Oscillations during In-Flight Piloting Exercises Using Dry EEG Sensor Recordings

Scholl CA, Chi YM, Elconin E, Gray WR, Chevillet MA, Pohlmeyer EA

38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, 16–20 August 2016, doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2016.7591719

High Precision Neural Decoding of Complex Movement Trajectories Using Recursive Bayesian Estimation with Dynamic Movement Primitives

Hotson G, Smith RJ, Rouse AG, Schieber MH, Thakor NV, Wester BA

IEEE Robot Autom Lett, 1(2):676–683 (2016)

Individual Finger Control of the Modular Prosthetic Limb using High-Density Electrocorticography in a Human Subject

Hotson G, McMullen DP, Fifer MS, Johannes MS, Katyal KD, Para MP, Armiger R, Anderson WS, Thakor NV, Wester BA, Crone NE

J Neural Eng, 13(2):026017 (2016)

Revolutionizing Prosthetics’ MindFlight: Brain Computer Interface Control of Multiple Simulated Aircraft

Rich MJ, Pino JA, Cybak D, Ellsworth J, Katta N, Koterba Z, Drake D, Fifer MS, Tenore FV, D’Angelo D, Collinger JL, Downey JE, Wabiszewski C, Weiss JM, Boninger ML, Beaty J, McLoughlin MP, Pohlmeyer EA

Third Annual BRAIN Initiative Investigators Meeting, Arlington, VA, 12–14 December 2016

Revolutionizing Prosthetics: Multi-Modal Sensory Perception

Fifer MS, Tenore FV, Pohlmeyer EA, Bensmaia S, Dohopolski C, Helder J, Johannes M, Katyal K, Wester BA, Flesher S, Weiss JM, Downey JE, Gaunt R, Collinger JL, Boninger ML, Beaty J, McLoughlin MP

Third Annual BRAIN Initiative Investigators Meeting, Arlington, VA, 12–14 December 2016

The Effects of Chronic Intracortical Microstimulation on Neural Tissue and Fine Motor Behavior

Rajan AT, Boback JL, Dammann JF, Tenore FV, Wester BA, Otto KJ, Gaunt RA, Bensmaia SJ

J Neural Eng, 12(6):066018 (2015)

Kernel Temporal Differences for Neural Decoding

Bae J, Sanchez Giraldo LG, Pohlmeyer EA, Francis JT, Sanchez JC, Príncipe JC

Comput Intell Neurosci, 2015:481375, doi: 10.1155/2015/481375 (2015)

Long-Term Stability of Sensitivity to Intracortical Microstimulation of Somatosensory Cortex

Callier T, Schluter EW, Tabot GA, Miller LE, Tenore FV, Bensmaia SJ

J Neural Eng, 12(5):056010

Behavioral Assessment of Sensitivity to Intracortical Microstimulation of Primate Somatosensory Cortex

Kim S, Callier T, Tabot GA, Gaunt RA, Tenore FV, Bensmaia, SJ

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 112(49):15202–15207 (2015)

Sensitivity to Microstimulation of Somatosensory Cortex Distributed over Multiple Electrodes

Kim S, Callier T, Tabot GA, Tenore FV, Bensmaia, SJ

Front Syst Neurosci, 9:47 (2015)

The Effect of Chronic Intracortical Microstimulation on the Electrode-Tissue Interface

Chen KH, Dammann JF III, Boback JL, Tenore FV, Otto KJ, Gaunt RA, Bensmaia SJ

J Neural Eng, 11(2):026004 (2014)

Collaborative Approach in the Development of High-Performance Brain–Computer Interfaces for a Neuroprosthetic Arm: Translation from Animal Models to Human Control

Collinger JL, Kryger MA, Barbara R, Betler T, Bowsher K, et al.

Clin Transl Sci, 7:52–59, doi: 10.1111/cts.12086 (2014)

Approaches to Robotic Teleoperation in a Disaster Scenario: From Supervised Autonomy to Direct Control

Katyal KD, Brown CY, Hechtman SA, Para MP, McGee TG, Wolfe KC, Murphy RJ, Kutzer MDM, Tunstel EW, McLoughlin MP, Johannes MS

IEEE Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Chicago, IL, 14–18 September 2014, pp. 1874–1881

A Collaborative BCI Approach to Autonomous Control of a Prosthetic Limb System

Katyal KD, Johannes MS, Kellis S, Aflalo T, Klaes C, McGee TG, Para MP, Shi Y, Lee B, Pejsa K, Liu C, Wester BA, Tenore F, Beaty JD, Ravitz AD, Andersen RA, McLoughlin MP

IEEE Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, San Diego, CA, 5–8 October 2014, pp. 1479–1482

Demonstration of Force Feedback Control on the Modular Prosthetic Limb

McGee TG, Para MP, Katyal KD, Johannes MS

IEEE Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, San Diego, CA, 5–8 October 2014, pp. 2833–2836

Behavioral Demonstration of a Somatosensory Neuroprosthesis

Berg JA, Dammann JF, Tenore FV, Tabot GA, Boback JL, Manfredi LR, Peterson ML, Katyal KD, Johannes MS, Makhlin A, Wilcox R, Franklin RK, Vogelstein RJ, Hatsopoulos NG, Bensmaia SJ

IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng, 21(3):500–507 (2013)

High-Performance Neuroprosthetic Control by an Individual with Tetraplegia

Collinger JL, Wodlinger B, Downey JE, Wang W, Tyler-Kabara EC, Weber DJ, McMorland AJ, Velliste M, Boninger ML, Schwartz AB

Lancet, 381(9866):557–564 (2013)

Simultaneous Neural Control of Simple Reaching and Grasping with the Modular Prosthetic Limb using Intracranial EEG

Fifer MS, Hotson G, Wester BA, McMullen DP, Wang Y, Johannes MS, Katyal KD, Helder JB, Para MP, Vogelstein RJ, Anderson WS, Thakor NV, Crone NE

IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng, 22(3):695–705 (2013)

HARMONIE: A Multimodal Control Framework for Human Assistive Robotics

Katyal KD, Johannes MS, McGee TG, Harris AJ, Armiger RS, Firpi AH, McMullen DP, Hotson G, Fifer MS, Crone NE

6th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER), San Diego, CA, 6–8 November 2013, pp. 1274–1278

Demonstration of a Semi-autonomous Hybrid Brain–Machine Interface using Human Intracranial EEG, Eye Tracking, and Computer Vision to Control a Robotic Upper Limb Prosthetic

McMullen DP, Hotson G, Katyal KD, Wester BA, Fifer MS, McGee TG, Harris A, Johannes MS, Vogelstein RJ, Ravitz AD, Anderson WS, Thakor NV, Crone NE

IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng, 22(4):784–796 (2013)

Revolutionizing Prosthetics—Phase 3

Ravitz AD, McLoughlin MP, Beaty JD, Tenore FV, Johannes MS, Swetz SA, Helder JB, Katyal KD, Para MP, Fischer KM, Gion TC, Wester BA

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 31(4):366–376 (2013)

Restoring the Sense of Touch with a Prosthetic Hand through a Brain Interface

Tabot GA, Dammann JF III, Berg JA, Tenore FV, Boback JL, Vogelstein RJ, Bensmaia SJ

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, doi:10.1073/pnas.1221113110 (2013)

Recent Enhancements to Mobile Bimanual Robotic Teleoperation with Insight Toward Improving Operator Control

Tunstel EW, Wolfe KC, Kutzer MDM, Johannes MS, Brown CY, Katyal KD, Para MP, Zeher MJ

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 32(3):584–594 (2013)

Experimental Validation of Imposed Safety Regions for Neural Controlled Human Patient Self-Feeding Using the Modular Prosthetic Limb

Wester B, Para M, Sivakumar A, Kutzer M, Katyal K, Ravitz A, Beaty J, McLoughlin M, Johannes M

IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–8 November 2013, paper MoBT9.6

Biomedicine: Revolutionizing Prosthetics—Guest Editors’ Introduction

Smith DG, Bigelow JD

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 30(3):182–185 (2011)

Revolutionizing Prosthetics: Systems Engineering Challenges and Opportunities

Burck JM, Bigelow JD, Harshbarger SD

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 30(3):186–197 (2011)

A Real-Time Virtual Integration Environment for Neuroprosthetics and Rehabilitation

Armiger RS, Tenore FV, Bishop WE, Beaty JD, Bridges MM, Burck JM, Vogelstein RJ, Harshbarger SD

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 30(3):198–206 (2011)

An Overview of the Developmental Process for the Modular Prosthetic Limb

Johannes MS, Bigelow JD, Burck JM, Harshbarger SD, Kozlowski MV, Van Doren T

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 30(3):207–216 (2011)

Control System Architecture for the Modular Prosthetic Limb

Bridges MM, Para MP, Mashner MJ

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 30(3):217–222 (2011)

Revolutionizing Prosthetics: Neuroscience Framework

Levy TJ, Beaty JD

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 30(3):223–229 (2011)

Revolutionizing Prosthetics: Devices for Neural Integration

Tenore FV, Vogelstein RJ

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 30(3):230–239 (2011)

Revolutionizing Prosthetics 2009 Modular Prosthetic Limb–Body Interface: Overview of the Prosthetic Socket Development

Moran CW

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 30(3):240–249 (2011)

The Cosmesis: A Social and Functional Interface

Biermann PJ

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 30(3):250–255 (2011)

Advanced Explosive Ordnance Disposal Robotic System (AEODRS): A Common Architecture Revolution

Hinton MA, Zeher MJ, Kozlowski MV, Johannes MS

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 30(3):256–266 (2011)

Revolutionizing Prosthetics 2009: Dexterous Control of an Upper-Limb Neuroprosthesis

Bridges M, Beaty J, Tenore F, Para M, Mashner M, Aggarwal V, Acharya S, Singhal G, Thakor N

Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig, 28(3):210–211 (2010)

The list of papers linked below are closely related to the Revolutionizing Prosthetics program. The authors are affiliated with program partners or associated organizations. This listing is not all-inclusive, and some research cited was sponsored by non-DARPA organizations.