News

60 Years on, Nuclear Power Still Enables Pioneering Space Missions

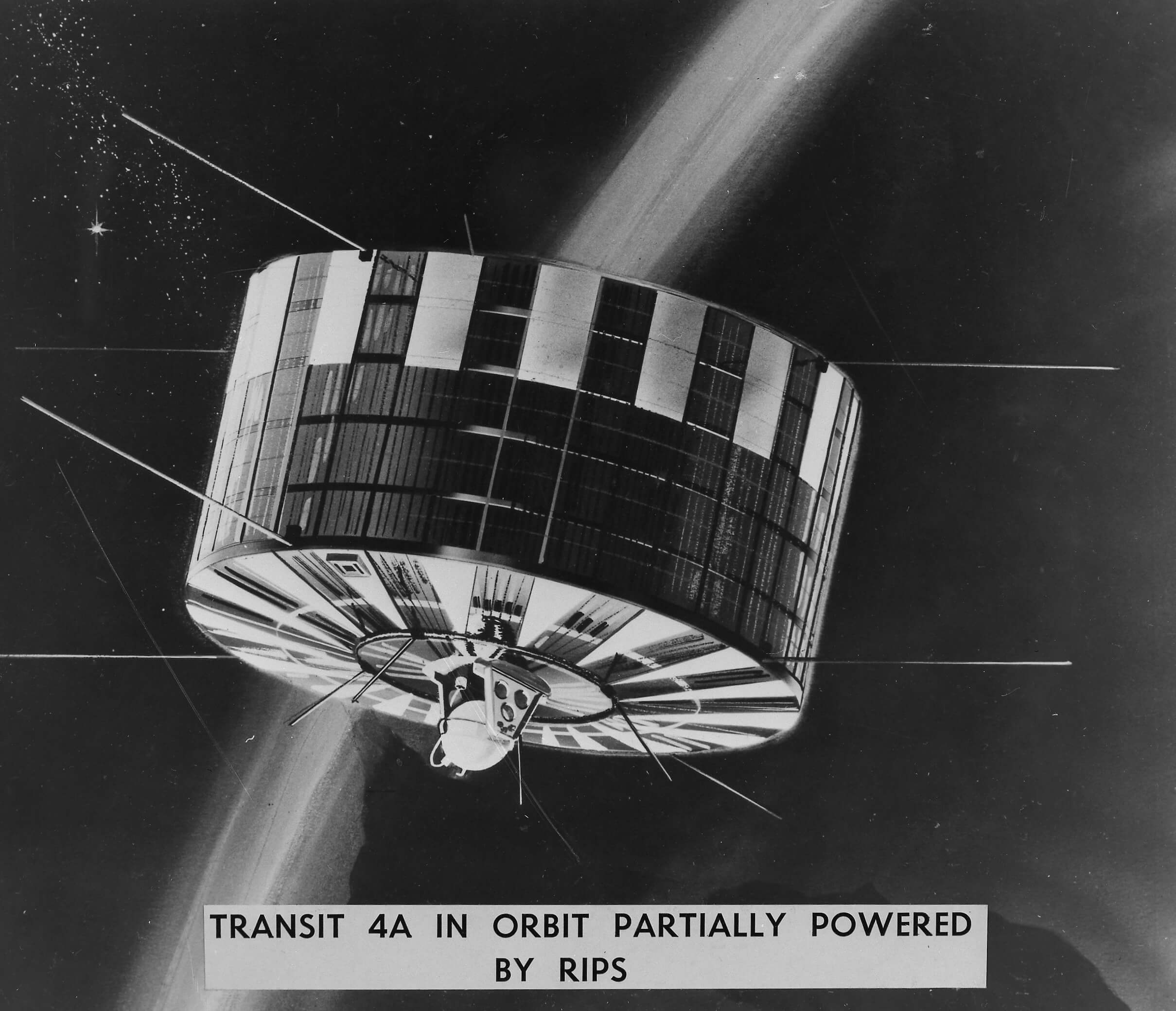

Sixty years ago today, the United States launched its first nuclear-powered satellite into space, opening a new era that has enabled us to explore the nearest and farthest reaches of our solar system.

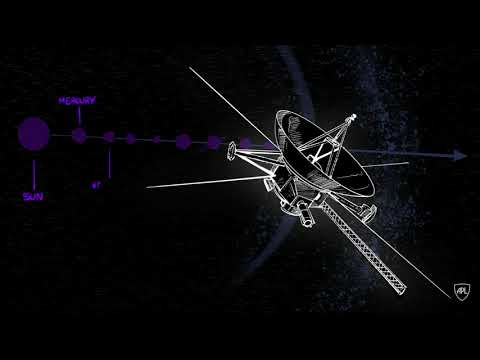

To date, radioisotope power systems (RPSs) have powered more than two dozen U.S. space missions, from the first U.S. landers to touch the Martian surface to the Pioneer 10 and 11 and Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft that provided the first detailed glimpses of the outer planets and edge of our star’s influence.

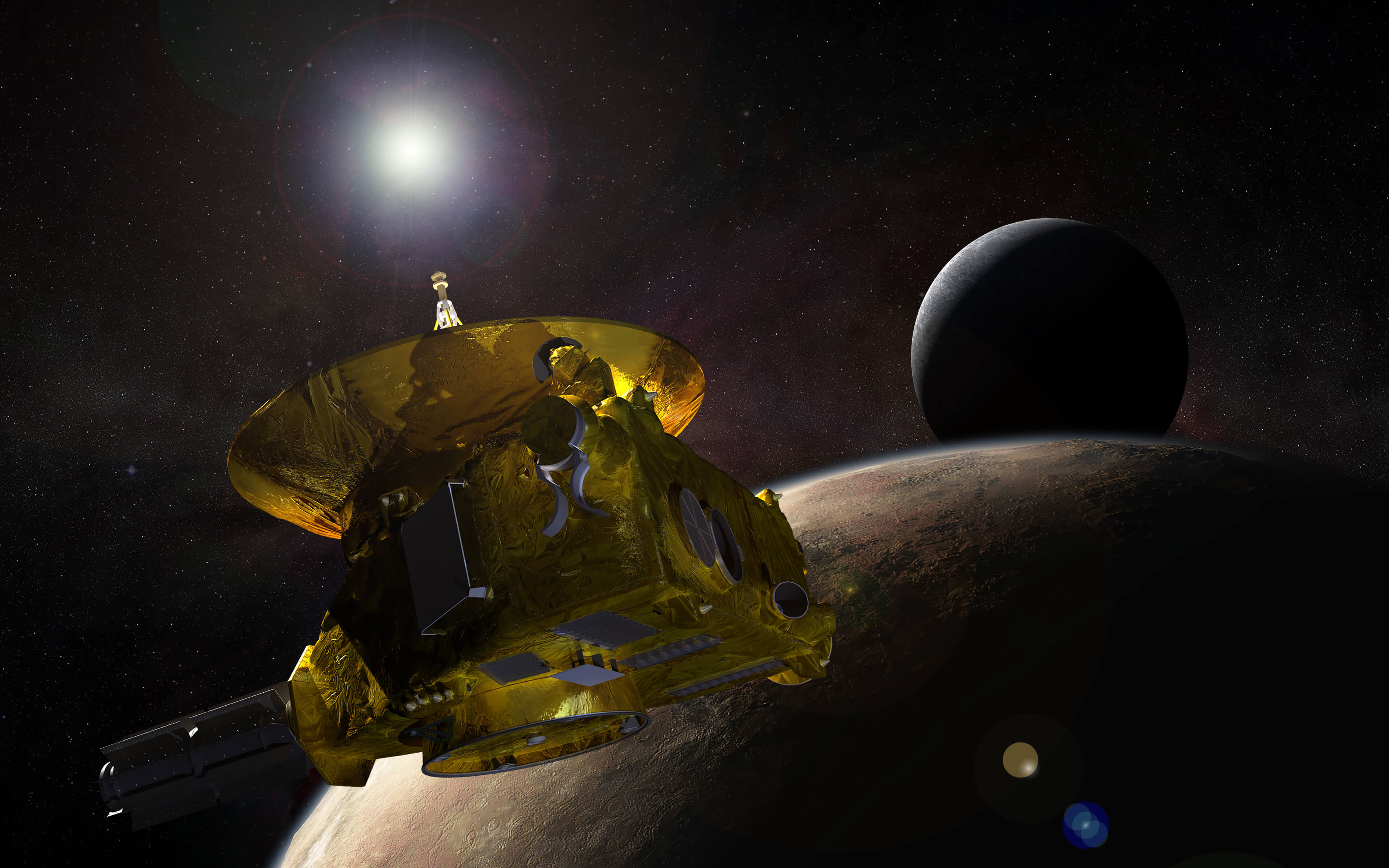

“If it hadn’t been for RPSs, you wouldn’t have flown Ulysses to the Sun’s poles, or Cassini to Saturn, or New Horizons to Pluto — and you wouldn’t be flying Dragonfly to [Saturn’s moon] Titan,” said Ralph McNutt, a space physicist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). “That’s why it’s called an ‘enabling technology’ — it means there really isn’t any other way to do it.”

RPSs use plutonium-238 pellets, a radioactive fuel produced by facilities of the U.S. Department of Energy. As the plutonium naturally decays, it releases heat, which thermoelectric converters use to generate electricity.

Over the last 60 years, APL has launched seven spacecraft carrying nuclear power supplies, with plans to launch another in 2027. Here’s a look at four of these missions and how RPSs made (or will make) them possible: